[Free to read] Musica Humana: How to Make Your Soul Sing

How maths, music, the rhythms of the planets, and depth psychology can help you lead a harmonious life.

This year I’ve had 9 dreams featuring guitars–an unusually high number given that I don’t really play this instrument or own one anymore.

The theme appears to be the same. In each dream, I find myself in an odd place where I discover one or more guitar-like instruments: pear-shaped ouds, fancy lutes, sitars, mini-guitars, even an acoustic guitar I had in my home growing up. I feel delighted to find the instruments, yet there’s a sense that my parents don’t want me to find them. I’m intrigued. I want to play them, but I’m not sure how.

And then came a dream charged with a different feeling-tone than the rest:

I’m in my dad’s garage and I find some guitar-like instruments. One of them looks like an oud and has seven strings: one bass string that makes an Arabic sound, then 2 electric strings, then maybe another solo electric one. Some strings are solo and some are in pairs. I start playing the highest string, the seventh, which is oddly the thickest bass one, and I start singing “Alllaaaaaah” along with it. I’m having a lot of fun. I’m fascinated by the mix of strings and I want to figure out the tuning.

I woke up feeling energised and very moved by the song that came out of me: why Allah? Why the odd combination of strings? Why electric and acoustic? How come the last string was the thickest and lowest in tone? And where could I get my hands on such a wonderful instrument?

Immediately, this instrument felt very important. The seven strings led me to the idea of chakras: the seven energy centres of the body that vibrate to their own frequencies. In this system, the seventh chakra, also known as the crown chakra (or Sahasrara in Sanskrit) corresponds to our connection to the higher realms, unity consciousness, and the idea of god.

I already knew from my acupuncture sessions that some of my chakras are more “electric” than others, causing a bit of an imbalance in my system. Indeed, I can easily slip into being rather heady and dreamy, getting caught up in ideas and losing touch with my lower needs.

With this in mind, my dream seemed to call me to attune or rebalance my chakras. If I’m the guitar in the dream, perhaps I play best when I reconnect with my higher purpose, represented by the thickest string and seventh chakra, and allow that to resonate through me.

However, it didn’t explain why I was singing “Allah” and not “god”, “Buddha”, “Christ” or even “Brahman”–words for god that are part of my spiritual upbringing or recent practice. I’m not Muslim and I don’t read much Sufism. The interpretation was helpful, but it didn’t unlock the meaning of dream. And the dreams kept coming, signalling that there was more to this mysterious instrument than I originally thought.

Synchronicity: horizontal and vertical time

I find that something really beautiful happens when we truly engage with a dream. When we keep it in mind, it’s almost as if the whole unconscious mobilises to help us release the energy behind it.

Jungians call this synchronicity: an acausal organising principle in the universe where two events occur simultaneously. We often experience this when the outer world somehow mirrors something in our inner life, and it feels meaningful to us (there’s usually a release of emotion involved).

I find it helpful to think about causality and synchronicity as two ways of experiencing the world.

On the physical, horizontal plane, time is ruled by Chronos, hence things appear chronological and causal, following the laws of physics. I had this dream, which led me down a path of research, which led to me writing this essay, which is now perhaps sparking new ideas in your mind. You might talk about these ideas later to your date, who will be so impressed with your knowledge that they will ask you out again. A couple of years down the line you’re married to the love of your life because you read this essay–wait, maybe I’m getting too carried away here.

Then there’s the vertical plane of existence. Here, time takes on a whole new dimension as Kairos. Instead of flowing from past to future, events co-occur not because they cause each other, but because they share the same archetypal pattern.

For example, reading this essay may spontaneously spark an image in your mind or inspire a dream that is very meaningful to what’s preoccupying you. It won’t logically follow what you’re reading here, but it might make sense intuitively.

And so it happened here. Puzzled by the mysterious guitars, I felt moved to ask a lecturer at my training how he would work with such a dream. He told me about the music of the soul and the importance of going back in the dream to play the instrument. It entirely escaped my mind that this lecturer wasn’t just a psychotherapist, but also a Sufi teacher.

I wondered home thinking about the symbolism of music as the soul’s voice. Just as I was getting ready to sleep, I found my tired eyes fixate on a particular book that had been sitting untouched on my self for almost one year. As my index finger traced the contents page of Thomas Moore’s The Planets Within: The Astrological Psychology of Marsilio Ficino, a wave of emotion suddenly washed over me.

There it was: part 3, the music of the soul.

Three types of music

Music is everywhere today. If it’s not playing in our ears as we cruise through the busy cities we live in, it will be blaring through a cafe’s speakers, a shop, or some guy’s boombox as he cycles past us. It’s the background of ads, Instagram reels, or guided meditations. And it’s hard to remember that music wasn’t always profane.

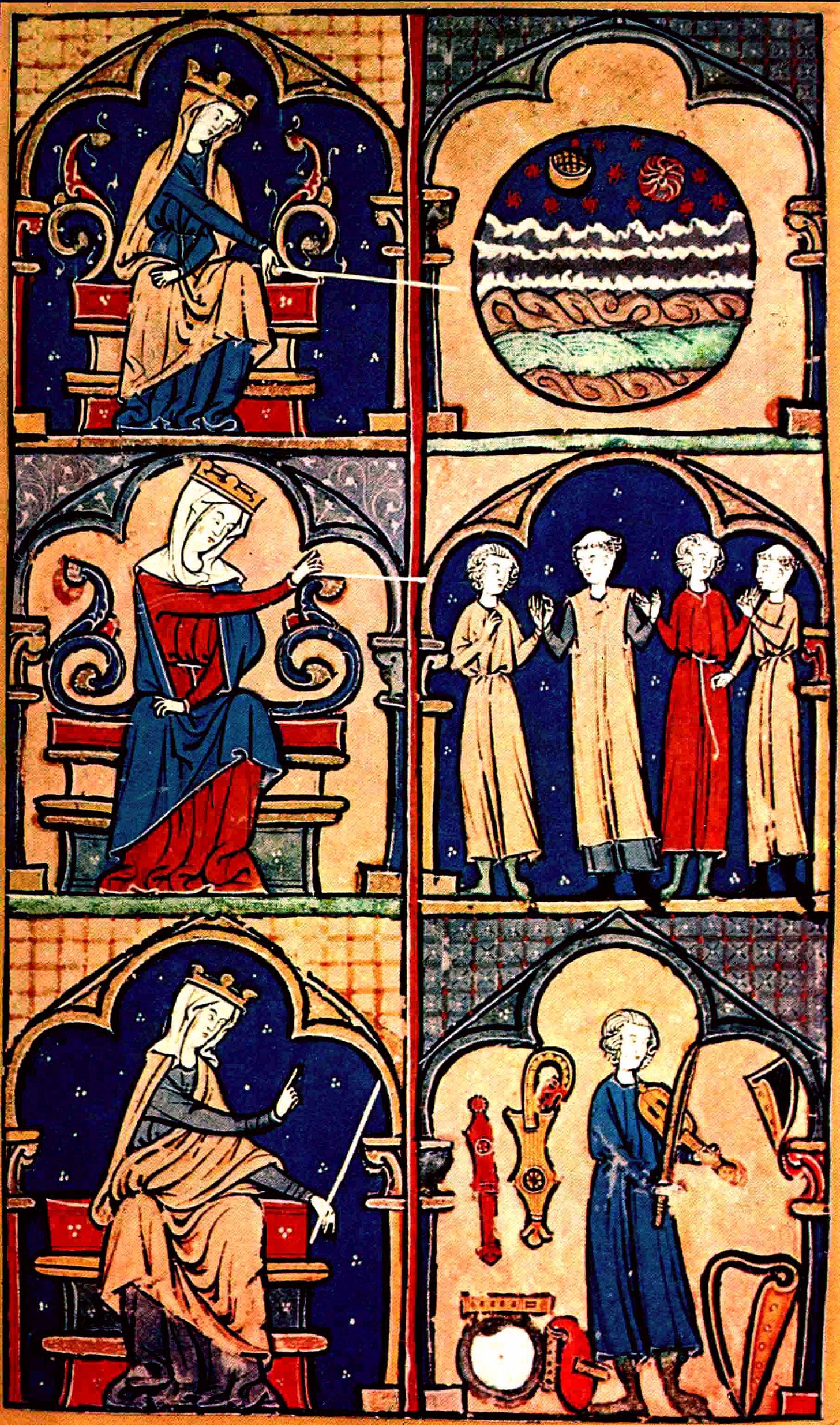

Interestingly, in medieval times, vocal or instrumental music was considered the lowest form of music. The Roman and Christian philosopher Boethius (ca. 480-524 AD), a student of Greek philosophy and neo-Platonist, coined three types of music:

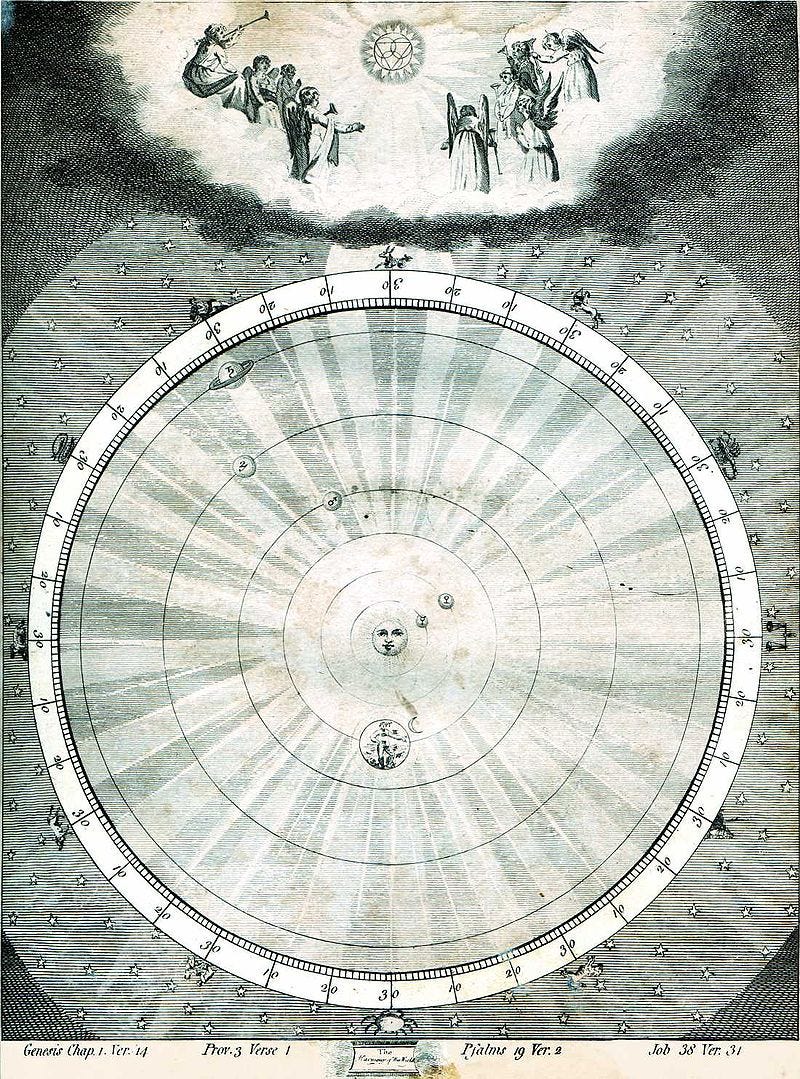

Musica mundana: the music of the universe, expressed in the rhythms of the planets. This the highest form of music.

Musica humana: human music or the music of the soul, as expressed through the moving patterns of inner experience, in the body.

Musica instrumentalis: vocal or instrumental music, the lowest form of music.

Of course, the three types of music exist at all times and are representations of each other. We might think of them vertically, as in the image below, as the same essential pattern of music taking on different dimensions on different planes of existence. The music of the universe is felt as an inner music that moves us, which we then create audibly with the help of instruments and the voice.

In depth psychology terms, we could say that the greater intelligence of the collective unconscious manifesting as archetypes (musica mundana) is felt internally as the complexes that form the personal unconscious (musica humana), which then manifest outwardly in our behaviour (musica instrumentalis). Everything around us, including ourselves, follows an archetypal pattern.

Harmony isn’t what you think

This idea doesn’t start with Jung’s concept of the archetypes or with Boethius. 900 years before Boethius, the Greek philosopher Pythagoras was already laying the foundations of musica universalis, or the music of the spheres.

Pythagoras observed that celestial bodies moved in a precise mathematical harmony. He also noted that everything in the natural world, on Earth, follows predictable patterns manifested as numerical proportions. This was particularly relevant in his experiments with musical tones, performed on an instrument he invented, called the monochord. He realised that the mathematical proportions between musical notes followed a similar pattern as the movements of the planets and the changes in the natural world.

However, the musical harmony Pythagoras experimented with was vastly different from how we experience harmony today.

While contemporary music follows a vertical arrangement of notes that lose their individual tone to form a new, single tone expressed as a chord, Pythagorean harmony is horizontal and relies on tones maintaining their separate integrity. Instead of chords, this harmony works with overtones and polyphony. To our modern ears, ancient Greek harmony may sound dissonant or odd, but it creates a much richer sound.

This idea was particularly developed by Marsilio Ficino–the man my mysterious book was about.

Portrayed by Thomas Moore in his book as a sort of magician-astrologer-music psychotherapist of the Renaissance, Ficino insisted that the music of the soul cannot be anything but dissonant. Just as musica mundana is harmonious because the planets maintain their separate integrity, so should we seek to arrange our inner lives by honouring the dissonance between all aspects of ourselves.

“He conceives human music as the proper arrangement of one’s life so that all concrete experiences resonate, like overtones, the fundamental octave of possibilities represented by the planet-tones.”

Thomas Moore, The Planets Within: The Astrological Psychology of Marsilio Ficino

It may not immediately seem so, but Ficino’s idea is radical.

In a world that praises integration and the harmonious unity of the personality, Ficino advises that we best honour our souls by remaining somewhat dissonant inside. Our personality doesn’t need to make sense or “sound good”, it needs to sound its true song, in its polyphony. A musical soul is one that honours the voice of each inner aspect (symbolised for him as the archetypal planets) just as it wishes to express itself.

And this can completely change how we think about our lives.

Recovering the soul harmony

Ficino’s ideal of becoming well-tempered and tuned reminds me of my mysterious guitar: the seven strings perhaps symbolising not just the chakras, but the seven planets that govern us. The guitar doesn’t need tuning or tempering with. Only an immature ego would think that it knows better what true harmony sounds like. A mature ego serves the soul by listening to its unique song.

This idea resonates with me deeply. As a psychotherapist, I found myself resisting any approaches or invitations from clients to “fix”. Getting rid of symptoms like anxiety or depression with meds and routines and other quick fixes sometimes (not always) feels like robbing people of a profound process of getting to know who they really are.

Ficino’s ideas take us back to a time where the gods–yes, plural–still lived amongst us. The polytheistic psyche of the ancient Greeks or Romans allowed humans to see all aspects of themselves mirrored in the divine drama. After all, the gods weren’t perfect: they were often envious, cruel, competitive, vain. They moved across the skies as symbolised by the planets and they affected what happened below.

This didn’t mean that people didn’t take responsibility for their actions (sorry I was two hours late, Mercury’s in retrograde again)–quite the opposite. Knowing how much they depended on the gods and how the gods depended on them, they participated in the divine drama by giving each god its due.

“A polytheistic psychology, in which all the gods and all sides of them, are tempered or tuned in, does not appear so insanely wholesome and positive, and in fact does not impose such a glorious yet demanding morality.”

Thomas Moore, The Planets Within: The Astrological Psychology of Marsilio Ficino

The advent of Christianity made polytheism unholy and replaced the gods with the one, father-like god who will punish anyone who dares to praise other gods other than him. Christianity really had its cake and ate it too: it appropriated astrology into itself while also forbidding anyone else from practicing it and calling it blasphemous.

Within us, this became instilled as a monotheistic inner rule: a need to remain harmonious with a patriarchal expression of the divine. Our idea of wholeness became rigid, perfectionistic, and rather unimaginative. We became fixated on bettering ourselves and lost the quest of knowing ourselves. The music of our souls become monotone.

To rescue our soul’s song, musica humana, we need to reconnect with our inner polytheism. As advised by James Hillman, we need to recover our tolerance for “the non-growth, non-upward, and nonordered components of the psyche”. This means getting comfortable with some of our inner dissonance and tempering, not tampering with our eccentricity.

Polytheism is not a religious or philosophical outlook. It’s a way of being that acknowledges inner multiplicity–the myriad complexes or parts within us, without suppressing them or forcing them into a cohesive identity.

This doesn’t mean that we remain fragmented selves. When we bring consciousness to these parts, we can acknowledge the archetypes or gods seeking expression through them. We don’t have to remain Saturnian, hard-working and moody, or only Venusian in our concerns with looking beautiful and being liked. We can make space in our lives so that Saturn and Venus can co-exist and sing their unique songs, along with the other gods.

By letting each god sing its song through us, we leave the superficial personas aside and begin to live with depth and consciousness. We reclaim our seat as participants in the divine drama of life, where the gods speak to us through dreams and synchronicity and help us find our own music.

And mysteriously, we find that we become much more integrated than before.

“What do you do if you aren't interested in cure, if you respect symptoms? The answer is that therapist and patient are quite active in their respective chairs riding the moods and fantasies of the anima, reaching for their assigned masks, incubating in the dreams, and entering the mythic drifts of life's episodes.”

James Hillman, A Blue Fire

I hope you enjoyed this essay and the story that led me to discover these ideas. If you found this useful, please like it, share it, and let me know what you thought in a comment below. And if you liked it *a lot*, you can switch to a paid subscription, which will help me devote more time to write longform essays like this.

Watch this video exploration of Pythagoras’ music of the spheres through the ages.

I randomly discovered the monochord a year ago, long before I heard about Pythagoras’ music of the spheres, and became quite fascinated by the sound for meditation. One day I’d love to have one, but for now you can check out this video of a monochord table used for sound healing.

I also recommend listening to this Monochord Meditation playlist on Spotify.

What did ancient Greek music sound like? Some Oxford music nerds tried to recreate it and it’s quite cool.