When dreams leave

How not remembering our dreams can be a symptom of a larger issue and why we should pay attention.

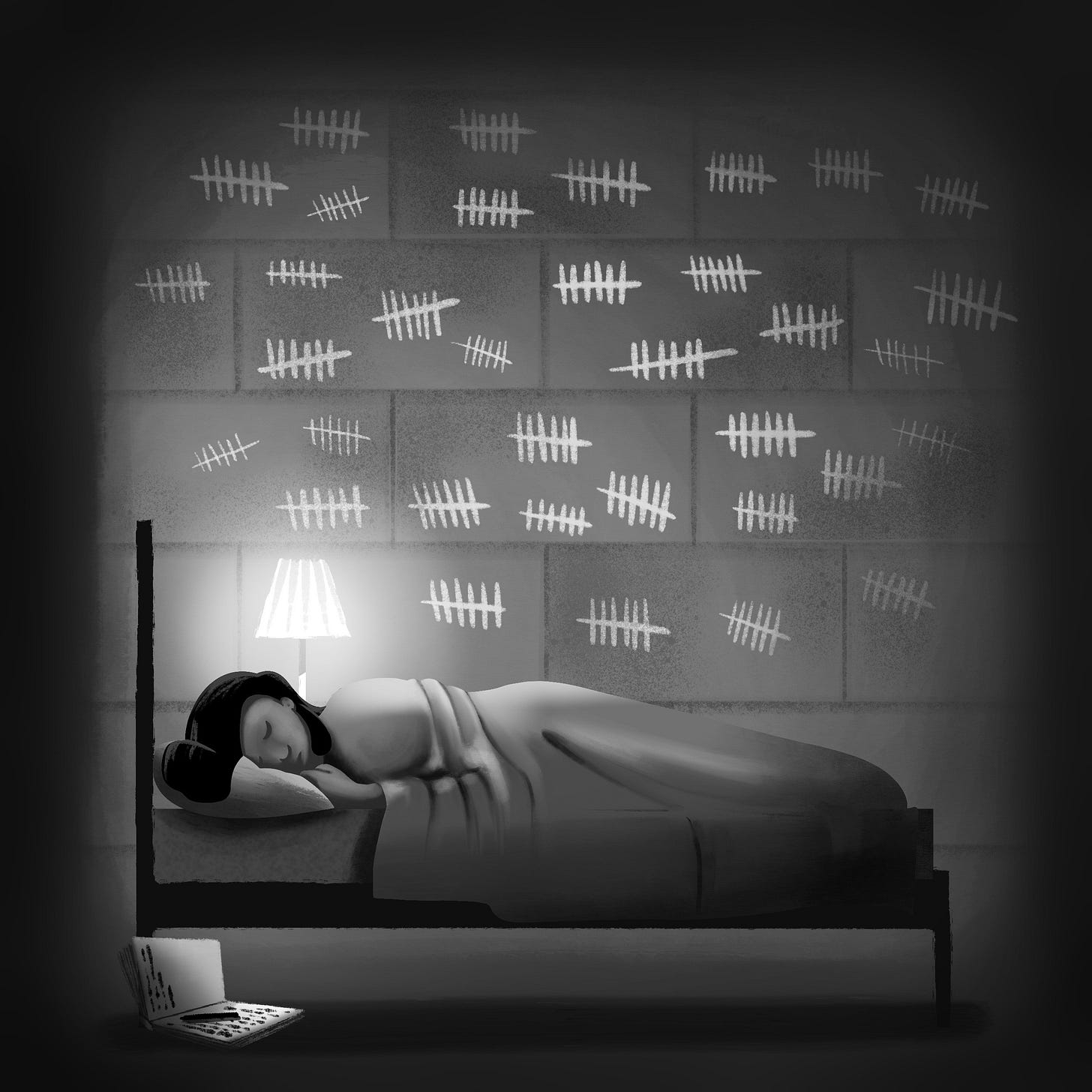

Last month my dreams left me. For a few weeks, I couldn’t hold on to any dream images, regardless of what I did. After about ten days of no dreams remembered, I began to feel uneasy and rather depressed: where had my dreams gone? Why was I being cut off from something so important to me? Had I done something to repel them?

In an attempt to bring my dreams back, I set out on a quest to find out why our dreams leave us and—more importantly—why aren’t we bothered about it?

As I searched for answers, I did recover my dreams—but I also realised that their absence holds more meaning than I first imagined. In the essay below, I’ll explore the psychological and cultural forces that disconnect us from our innermost selves by shutting off our dreams, the profound implications of this disconnection, and why, in today’s world, reclaiming them is an urgent act of resistance. After the paywall, I share some of my tips for dream recovery.

Quick note: I have one spot left in my 8-week (online) dream circle starting next Tuesday, 22 October. Sessions run for two hours every Tuesday evening, 7-9pm BST. You’ll be in an intimate, mixed group of therapists and laypeople, seasoned dreamers and beginners, all interested in diving deeper into their psyche through different experiential dreamwork methods, which I will introduce in each session. Get in touch if you’d like to join.

Part 1: The dream censor and the hostage self

Dreams don’t leave us accidentally. Just as the content of our dreams is rarely random, neither is their disappearance. Their absence points to deeper psychological dynamics that extend way beyond our sleep—most likely into every other aspect of our lives.

It was Sigmund Freud who first introduced the concept of the "dream censor”. Freud was right in believing that the unconscious mind communicates through dreams—however, he proposed that a "censor" steps in to distort or disguise any messages the conscious mind could find too threatening or uncomfortable. For Freud, the dream censor’s job was to make sure we sleep soundly, protected from the emotional distress of our repressions.

“This censor behaves analogously to the Russian newspaper censor on the frontier, who allows to fall into the hands of his protected readers only those foreign journals that have passed under the black pencil.”

(Sigmund Freud in “The Interpretation of Dreams”)

Today, we can look at the dream censor as less of a psychic gatekeeper, but more as part of a broader system of ego defences. When getting in touch with certain truths or parts of ourselves has been too unsafe, the ego can build barriers against them, sometimes to the point of blocking them altogether. Thus, stress-related dream loss serves a protective function—it can be incredibly helpful when you’re a child living in an unsafe environment or even an adult undergoing immense stress, trauma, or life transitions. In these instances, sacrificing the inner experience to adapt and survive difficult circumstances becomes necessary.

However, our defences tend to linger long after they’ve served their purpose. If neglecting the inner world becomes an ongoing way to cope with life, then the dream censor is no longer protective—it becomes restrictive.

This prolonged disconnection can lead to a life where the “censor” guards us from… well, ourselves. This can create a feeling that we’re our own worst enemy—that we’re somehow at war with our authentic self. Our dreams (if we remember them) can become nightmarish, depicting tortured people, trapped or neglected children, mutilated animals, or dying vegetation.

In Trauma and The Soul, Jungian analyst Donald Kalsched describes this dynamic using James Grotstein’s concept of the “hostage self”. Behind this rigid, military-like dream censor lies an essential part of ourselves that holds our innocence, creativity, and authenticity. Many writers associate this part with the inner child, the divine child, or the soul—all symbols of our innate wholeness.

However, when it comes to the hostage self, Kalsched and Grotstein depict this part of us more like an "undead child"—neither fully alive nor entirely gone, but trapped in a state of suspended animation. This is a response to severe trauma, where the psyche retreats inward, hiding this vital part of the self to protect it from further harm.

In Growing Big Dreams, dream writer and teacher Robert Moss echoes that the disconnection from our dreams mirrors the deeper loss of our connection to the divine child within. This may not seem like a big deal immediately. But seen though this lens, the loss of our dreams is also a loss of our capacity for imagination. When we stop dreaming, we stop seeing the world through a lens of possibility. We stop playing—which means that we stop trusting the world around us. Our vision becomes narrow and we can no longer see beyond our circumstances to change them. Life becomes dull, dutiful, and pointless, devoid of the magic and meaning.

It’s rather simple: when we lose our dreams, we lose ourselves. Whether the loss is self-inflicted or a mere adaptation to a traumatic past, it’s our responsibility to reclaim our lost selves.

But while this is an intensely personal journey, it’s also a battle against larger, insidious forces we rarely take into consideration, especially within a therapeutic framework. We live in a time where everything (our time, attention, and even our sleep) is commodified.

In the final part below, I propose that reclaiming our dreams isn’t just about personal healing—it’s a radical act of resistance against a culture that would have us live on autopilot, dissociated from the wisdom we all carry within.

Part 2: Who has time for dreams anyway?

For millennia, dreams were considered sacred experiences. Long before the advent of the scientific method and modern research, people intuitively understood their significance. They gathered in sacred places to collectively dream and seek healing, enlightenment, or divine guidance. They recognised that dreams are doorways to something eternal and mysterious within ourselves. As Kelly Bulkeley writes in Big Dreams: The Science of Dreaming and the Origins of Religion, “dreaming has something to do with the way religious ideas and feelings get started in people’s minds”.

Today, however, unless you’re in some form of therapy or you’re an artist with a self-reflective practice, it’s unlikely you will pay much attention to dreams. Maybe you recall one every now and then, but more often than not, you might shrug it off as nonsense. If you're somewhat psychologically inclined, you might even chalk it up to Freudian wish-fulfilment or suppressed anxieties. A nightmare might loom in your consciousness for a few days, darkening your mood, but even that will eventually be forgotten.

I’m not pointing the finger at you here—rather at how the world around us doesn’t leave much space for us to value our dreams.

And why would we value them? Dreams cannot be immediately monetised (although advertisers are working on this). They don’t obviously make us more productive or more excited about profit margins. If anything, they pull us away from our worldly concerns into a strange, mysterious, and often uncomfortable inner space where super-smart algorithms no longer dictate our longings.

Dreams may show us that we’re miserable in our jobs. That we don’t have nourishing relationships. That we’re with the wrong partner. That we’re (god forbid) the problem. That we have a crazy talent we need to develop in order to be truly happy in our life—and it might go against what our parents, friends, spouses, or society expect from us.

Dreams demand us to turn inwards and figure out who we really are—but who has time for all that when the latest project is due in the morning or the latest season of Love is Blind just came out? We live in an extremely extroverted culture where the inner experience is of little worth, unless it can be quickly commodified to boost our Instagram persona. We consume crazy amounts of content daily. Sometimes I wonder if we’re not treating our innermost truths just like the content we’re habituated to watch: thumbs down, swipe left, skip, scroll, next.

But it’s more than the uncomfortable truths that our dreams reveal. In order to dream, we first need to sleep—and here’s where things get complicated. Our culture doesn’t just devalue dreams; it devalues the very act of rest. In his latest book, The Spirituality of Dreaming, dream researcher Kelly Bulkeley reminds us that sleep isn’t as simple as deciding to go to bed on time:

“Those of us who live within this broad cultural ecosystem are encouraged to view sleep in negative terms, focusing primarily on what it does not involve. When we are sleeping, we do not work, shop, consume, travel, party, communicate, or use social media. Sleep is a desert of action, an annoying interruption of our most important, productive, and enjoyable activities.”

(Kelly Bulkeley in The Spirituality of Dreaming)

And while I don’t believe that blaming all our issues on late-stage capitalism is always the solution (everyone hates that person at the party), perhaps it is worth asking: what happens to our inner lives when we exist in a world that measures worth almost exclusively through external achievements? Do we lose more than just sleep when we unconsciously buy into this system?

It’s worth remembering, as Bulkeley argues, that sleep is not a non-action. Brain activity varies during sleep cycles, allowing for key processes of memory consolidation, emotional regulation, neurotoxin removal, synaptic pruning—and dreaming. Most of us understand the implications of sleep deprivation for our physical health, but we rarely consider that not sleeping enough also means not dreaming enough. And if dreaming is a profoundly spiritual, intimate, and non-commercial act, perhaps being deprived of it has much greater implications, both personally and collectively:

“So the simple answer to the question of who benefits from our sleep deprivation is: anyone who wants to hold power over someone else. It does not require an especially conspiratorial mind to see the potential for social exploitation in this. The more sleep deprived people become, the less capable they are of resisting, protesting, or even questioning the authorities who govern their lives. They lose their mental sharpness and become more vulnerable to political misinformation, financial scams, authoritarian ideologies, and workplace abuses.”

(Kelly Bulkeley in The Spirituality of Dreaming)

When we don't sleep, we don't dream. And when we don't dream, we lose touch with a vital part of our inner world. Dreaming is not just a biological process; it is a profoundly spiritual act that connects us to our deepest selves and to the collective unconscious. When we are deprived of dreams, we are deprived of the connection to the parts of us that connect us to humanity and the larger consciousness. We are deprived on knowing who we are.

Part 3: Dream recovery

Halfway through my dream drought (and after feeling miserable for long enough), I decided to approach my absence of dreams symbolically—almost as if it were a dream in itself. If this dream were speaking to me, what would it be saying?

So I got my calendar out and traced the time to when my dreams stopped. Looking back, I realised the drought began just after I took on a new freelance project. It was a painful decision marked by an inner conflict that had been causing me anguish for a while. I had promised myself that I wouldn’t take on advertising work anymore, yet in reality I felt like I didn’t have a choice: I needed the money to pay my rent, pay for my training, and generally survive.

The issue with this inner conflict was that I had been unwilling to risk trying anything different. I had been overriding my psyche’s profound rejection of this work—which I felt viscerally—lying to myself with each project that this would be the last. Then it hit me: even though I valued my inner world and intuition in principle, I was routinely going against them.

My quest to recover my dreams became a poignant illustration of my points above: that dream loss operates at the fine interplay between personal trauma and collective issues. The loss of self does not happen in isolation. Beyond our (bloody!) parents, there’s a whole system that shapes us and dictates what we worship—and I don’t think we always realise how much of a say we have in that.

Ironically, I believe that dreaming can be our way of remaining awake against the personal and collective forces that entrap us. It may remain one of the few ways we can hear our cry for authenticity and aliveness amongst the many voices of peer pressure, parental expectations, and whatever society deems as “normal”. And fighting to reclaim our dreams may be a much more revolutionary act than we imagine.

After the paywall, you will find my top tried and tested, research-backed tips for bringing back dreams and improving dream recall. If you’re not already a paid subscriber, you can unlock the tips for only £5/month, which will give you access to the whole library and will also support my writing.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Begin Again to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.