[Free to read] Scapegoating: A Myth for All Ages (Part 1)

An essay about the victims, scapegoats, and exiles within us.

There’s a saying in Romanian: if three people tell you you’re drunk… go home.

While this speaks volumes about the country’s drinking habits, it’s also reminiscent of a familiar theme in fairy tales. Things often come in threes when something new is emerging: three princes, three sisters, or three tasks that the hero(ine) has to complete. In my case, the threes happened all at once, over the span of a day and night.

As always, it all began with a dream:

I am at my old advertising agency, but somewhere high up in a NY-type skyscraper, and I see a satellite with a screen attached to it steadily coming towards the big glass wall. No one else seems to notice. I say out loud “wow, what if it touches it”, imagining that the glass wall would somehow bend inwardly, since it wasn’t firmly attached to the frame. Suddenly we all realise that’s exactly what’s happening and the satellite pushes slowly into the window, which bends and crashes loudly against the floor. The window breaks into small pieces but no one is hurt. Now the wall is just a huge open space and I can see the other skyscrapers and the sky.

I hear from someone that I am fired because the company has to blame someone for this and they chose to blame it on me. I’m furious because I had nothing to do with it other than seeing it happen. They tell me to leave everything behind and leave the place immediately, but I decide I actually want to take my backpack. A woman says they’re also going to sue me, which makes no sense and feels so over-the-top, since I didn’t do anything. All I leave behind is a purse that looks like a colon, with some of my faeces in it, which is growing bigger with gas almost as if it’s gonna blow up.

I didn’t make much of the dream and didn’t understand why I was blamed so unjustly for something I had nothing to do with. There were no obvious parallels in my waking life. I went about my day, picking up from where I left off in the astrology book I was reading at the time. Learning about scapegoating “signatures” in the natal chart, I was rather shocked to discover that the theme repeated three times in mine–something astrologers, much like Romanians in my example above, would advise that you go home and really think about.

But sometimes you just don’t get it. Within the space of a few hours you may get a dream and the same thing thrice repeated, and still not have it click. The penny dropped only later in the day, when I remembered I had picked up a random book from my training institute the previous night. Looking through the shelves of their book collection, I was in the mood to read something new and not too demanding (read: thin). Without paying much attention to the title, I found myself picking up a book by an author I had already enjoyed and that presented as non-threatening with its mere 110 pages.

As I rummaged through my backpack to find the book, I saw its title: The Scapegoat Complex by Sylvia Brinton Perera.

In this first essay in my series on scapegoating, I will be exploring some of the mythological, cultural, and psychological aspects of this fascinating phenomenon, as it’s been revealed to me through synchronistic dreams, books, and my clinical experience as a psychotherapist. Follow-up essays will focus on expanding on this theme and will be available for paid subscribers only.

The scapegoat myth

In its simplest definition, scapegoating is a form of shifting blame to another and punishing them for our sins. It’s a slightly more advanced and violent form of sweeping unpleasant things under the carpet. Instead of pretending something didn’t happen and letting the feelings rot in their shadowy place, scapegoating implies shifting our guilt and sins right onto the neighbour’s carpet–and then setting his house on fire.

It only takes a quick glance at the news headlines today to see that scapegoating is one of humanity’s go-to activities. In fact, evidence suggests that scapegoating might have been around for as long as we have, with evidence of such rituals going back thousands of years.

The name itself comes from the old Hebrew practice of using two goats for the ritual of redemption. Every year, a goat would be sacrificed on the altar in the name of Yahweh as a sin-offering, in the hopes that its blood would atone the community’s sins. Another goat, who was invested by the priest to carry the guilt of the community’s sins, would be expelled into the wilderness in the name of Azazel, the fallen angel.

Christianity makes use of the very same myth, creating the greatest scapegoat of all times as Jesus–the lamb of God (Agnus-Dei), sacrificed and exiled by his own father for the sins of humanity.

In the chapter dedicated to Law 26: Keep your hands clean from his book on power, Robert Greene quotes the Athenian habit of keeping a few weak and unproductive folks around, supported by public welfare, who were then sacrificed (rather violently) whenever the city was hit by extreme conditions like famine, plague, or natural disasters.

Athenians weren’t the only ones with this practice. Other powerful figures like emperors or politicians around the world have always sacrificed their most trusted advisors to satisfy (and quieten) the population threatening to uprise against the leader’s tyranny. The sacrifice often involved a public beheading, which the advisor accepted in return for their family being well taken care of.

Even today, political parties or corporations who attract more scrutiny than normal will usually publicly scapegoat a figurehead who gets removed from office, but rewarded in private. On a smaller scale, people like you and me regularly blame our failures on the weather, our parents, or planetary movements. In fact, any typos in this newsletter are entirely Mercury’s fault, not mine.

Humour aside, there’s something deeply dark about scapegoating. The old rituals dedicated to purging evil take on much larger and more threatening forms in our secular age. Our proclaimed rationality assumes that we have mastered our impulses and emotions, yet our actions as a global community prove otherwise.

Scapegoating, evil, and shadow denial

Plenty of similar stories abound in history, revealing great figures of power sacrificing innocent beings to banish sin from the community. Scapegoating has served as a way for humans to deal with something that’s far too big, too terrifying, and too difficult to comprehend: evil.

As I previously wrote, it takes psychological maturity and nuance to confront evil. This is a challenge especially in a culture shaped by monotheistic religion, which relegates evil to the shadow, sweeping it under the psycho-spiritual carpet. This encourages a misunderstanding of evil as something that only exists in the absence of good–that as long as we’re good girls and boys, we can’t be bad. Evil won’t touch us if we obey the rules.

But evil is always around. Some etymologists even trace the word’s roots back to the Proto-Indo-European root upo, which means down, up, over–it’s right by your side. Interestingly, the word upelos from the same root refers to evil as going over or beyond the limits. This gives us another hint about what evil might be, as psychological inflation, also known as identification with an archetype.

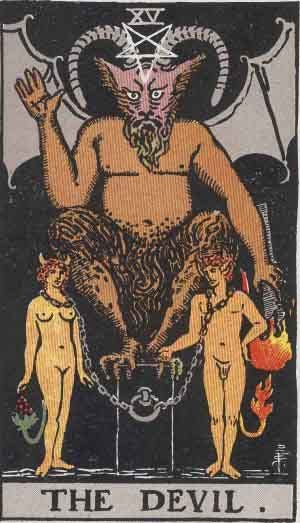

Most of us don’t have the tools to recognise evil as an archetypal force which can seduce and possess us. We think of evil as some obviously vile force wearing an SS uniform and calling a parade to announce its presence. We expect to see an ugly, horned man, with talons for feet and an icy glare–but evil is far more elusive.

Examining historical events of great evil reveals that this inflation can come in many forms. The archetype can come in the guise of justice, a seemingly positive ideal for society, the fight for equality, beauty, purity, even “doing the right thing”. Ideas can infuse us with such archetypal power that we feel like gods–we lose our humanity and so we find it easier to dehumanise others in the name of an ideal. We can feel so righteous in our convictions and ready to wipe out anyone who opposes them.

By banishing evil from the collective consciousness, we simply remain unaware of it and become ill equipped to deal with our own drives for power. For us to remain good, someone else has to carry the bad–we enact the same ritual as many civilisations did before us, only that we do it unconsciously.

This constellates a huge shadow, both personally and collectively. Instead of participating in a sacred ritual that acknowledges our wrongdoings and asks for redemption, we simply transfer them to others. Minorities, children, or anyone who can’t defend themselves become scapegoats for what we can’t own in ourselves. What used to be ritual is now compulsion. We merely pass the complex forward, to the next unfortunate scapegoat.

Writing about his hopes for the Age of Aquarius, Jung called for the importance of bringing consciousness to the way we split off our shadow:

“It will then no longer be possible to write off evil as the mere privation of good; its real existence will have to be recognised. This problem can be solved neither by philosophy, nor by economics, nor by politics, but only by the individual human being, via his experience of the living sprit.”

(CG Jung in Aion)

If we want scapegoating to cease on the global scene, we need to start taking evil seriously by acknowledging the archetypal core that exists within us all, individually. As a retreat participant said after emerging from a challenging psychedelic experience: you can’t keep laughing in the Devil’s face. The Devil needs respect.

If you’re interested in this theme, I’m excited to announce two upcoming workshops where you can engage with it:

I’m teaching a two-hour class on Healing the Mythic Scapegoat on Sunday, 5 May, from 7pm BST. This will be a mix of theory and experiential practices, with an emphasis on healing the complex and approaching it through dreams. The class is free to attend for Dreamwork Circle members and open to non-members for just £20. Substack paid subscribers get 25% off all my classes with the code at the bottom of the page (reply to this email to get the discount code code).

I’ll be leading an experiential two-day workshop on this theme as part of my final stage of qualifying as a psychotherapist. The workshop will take place in person, in London, sometime in the second part of the year and will be offered at a very low fee. It will be an opportunity to work with key aspects of the scapegoat pattern in yourself from a transpersonal perspective, using modalities like art and visualisation. If you want to be notified when registration opens, please sign up to this interest list.

Scapegoating in families

As with all archetypes, scapegoating manifests on all levels. What plays out on a global level also happens within a smaller community at school or work, a family, and inevitably within the individual’s psyche as he internalises the archetype.

It’s hard to know whether large-scale scapegoating starts out within families or is a result of a collective phenomenon contaminating the individual psyche. This strikes more as a chicken or egg dilemma, so I’ll leave it for another time (but if you have any ideas, please let me know in the comments!).

However, as a psychotherapist, I am much more interested in the unconscious forces that move a parent to scapegoat their own child–and the equivalent response from the child who accepts the unfair abuse and identifies with it.

Jung believed that, in the modern world, the scapegoat complex is no longer a sacred ritual of atonement, but originates in projecting the Self onto our parents or the collective. Driven by a sense of belonging, we adhere to the rules of the family or group, following its commandments and ideals. These become an image of wholeness driven by perfectionistic ideals: this is how I need to be.

But wholeness inevitably contains shadow–and rigid, monotheistic rules cast a rather large one.

In the family, the shadow includes the parents’ unrealised potentials, as well as their disowned impulses–whatever doesn’t fit with the inherited collective image both within society and within their own families (signalling that they have been scapegoats themselves). Normal, healthy impulses like aggression, desire, affection, playfulness, dependency, love etc. become repressed in favour of a perfectionistic, collectively dictated ideal of what it means to be good.

So what happens when a child, who hasn’t yet learned the to obey the collective commandments, comes into a family ruled by collective values? What happens when he notices and points out the family’s shadow, just like I did in the dream at the start of this essay?

The “uncivilised” child expresses its natural impulses unabashedly, which triggers the parents’ shadow. He may question the parents’ way of doing things and point out the inconsistencies they desperately try to hide (Daddy drinks a lot. Mummy lies.). Thus, the parents feel threatened by the child–even though what he’s doing is not dangerous in itself. The child may want to play freely, be naked, be creative or truthful, or express his love in a physical manner to the parents. If the instinct has been denied in the family, the parents’ shadow is constellated, but they’re too unconscious to own and integrate it. The internal threat is thus felt as an outer one and the shadow gets projected onto the child, who is punished and shamed for the parents’ sins.

Most of us experience this growing up as strict, punishing parents who instil a great fear of “what the neighbours might think”. In religious households, the Self is projected onto God, who’s perceived as always watching and keeping tabs. The Self can also represent the imagined reputation of the family within the community, especially if the parents are somewhat public figures.

In more extreme cases, the parents feel so threatened by the child’s impulses that they respond defensively, instilling a fear in the child of their own nature. Such children end up routinely accused for the parents’ moods (You made me angry), mistakes (I broke this glass because of you), lack of empathy (Stop crying or I’ll give you a reason to cry), marital failings (Your dad left you because you’re a bad boy) or even violent outbursts (Look what you made me do!).

The psychology of the child scapegoat

Thus, the child is not seen for who he is and is punished for things he hasn’t done. He ends up carrying and identifying with a shadow much too big for a human. Inevitably, the child fails to develop a full sense of self and grows up with many splits in his personality that he may not even be aware of. Depending on his nature, he grows up to be the perpetual victim or martyr or even an accusing scapegoater to those he perceives as weaker than him.

More than that, the scapegoated chid develops into a complex and often traumatised adult at odds with himself. The Hebrew myth discussed above gets reenacted psychologically in the inner world of the scapegoated individual.

Just as one goat had to be sacrificed to please the angry god, a part of the scapegoated individual’s psyche has to carry the immense pain of being rejected, abused, and punished by the group. This part feels victimised and usually retreats into the unconscious to protect the individual from getting in touch with the emotions.

Another part takes on the role of the sin-carrier, exiled goat. This part identifies with the family’s projections and carries their shadow. It feels innately bad, rotten, eternally damaged for the denied impulses. Because it identifies with a larger shadow than human, this part (and therefore the individual) suffers from negative inflation–it feels masochistically grandiose, capable of carrying anyone’s shadow as it considers itself stronger than others.

In addition to the two inner goats, the myth’s wholeness is completed by an internalised accuser and a persona-ego. The first stands for the priest in the myth, represented by the judgmental voices of the parents and the collective that the scapegoated child internalises as his own.

Far too split to develop an ego, the child compensates for this chaotic and painful inner world by constructing a persona-ego: a chameleon-like persona that adapts to whatever situation he’s in, ensuring that he’s acceptable. The persona-ego often presents as good, obedient, stoical, and pleasing. He’s cool. Paradoxically, this both saves the scapegoated person from further harm and entraps him in the dynamics of the complex, as he eventually begins to identify with it and forgets that there’s a true self inside.

Coming up next

How is the child chosen as scapegoat? What psychological traits make you vulnerable to being scapegoated? How does a scapegoated person identify with the shadow? How does such a person develop in adulthood and what difficulties might they encounter?

And, most importantly, how can the scapegoated individual heal?

I will be exploring these questions in the next few essays, which I aim to release a week or so apart from each other.

These essays will be paywalled, so if you’d like to learn more about the fascinating world of the scapegoat and support me writing such in-depth material, please upgrade to a paid subscription for only £5/month.

Your turn: what’s your relationship to scapegoating?

I would also love to hear from you, subscribers. Did you connect with the theme discussed here? How is scapegoating present in your life? What have you done to overcome it?

Like, share, and leave a comment below.

Thank you for sharing this powerful piece. It is beautifully written and speaks to the importance of the parent-child dynamic, specifically the impact of unconscious thoughts, the psyche, intergenerational trauma, and "hauntings." Parents hold responsibility for engaging in mindful parenting and their own psychotherapeutic work. In the absence of working through (becoming conscious of) projections and taking ownership of them, parents unconsciously project onto their children (and their children) perpetuating a vicious cycle. And yet, Healing is possible and powerful, if the work is done.

I resonated with some of the things included in the article namely - "the parents feel so threatened by the child’s impulses that they respond defensively, instilling a fear in the child of their own nature" and "The persona-ego often presents as good, obedient, stoical, and pleasing." I didn't understand my need to fit in at all costs until I started therapy and some of the experiences I had growing up got to be reframed which shifted the blame from my parents into ownership as an adult for the past. It's not an easy feeling to live with and you explained it beautifully that it helps and harms the person that is staying in this complex. Looking forward to the next articles!

P.s. you made me look up scapegoating “signatures” in the natal chart :) thanks for the 'prompt'!